Journal Entry 17 November

Preamble: What’s my next project all about?

I’m slightly older, fatter, grayer, not necessarily any wiser, but I now have three seasons of measurements of carbon particulates in Antarctica: and the basic result is that despite the extremely pristine nature of the Antarctic ‘natural background’ atmosphere, the manner in which human activities are conducted there leads to substantial and sometimes excessive concentrations of fumes and smoke in the living and working environment. Some of these emissions and human exposures are inevitable, some of them could be reduced or mitigated if anybody cared. For the most part, they don’t or can’t care, it’s part of the experience of being on The Ice. Most of the contract workers are young and macho, most of the managers are older and macho: all are trying to meet tough goals under harsh conditions and a little bit of smoke in the air ain’t gonna slow them down. If the C-130’s belch exhaust because their turbines are of an old design, well, the brown cloud over Williams Field at McMurdo will blow away soon enough. If tractor fumes get trapped inside the dome at Pole, well, the doctor has already learned to keep all gauze and bandages and supplies in ziplock bags, because everything gets covered with a thin film of soot. Until recently, our operations in Antarctica had been essentially run by the US Navy: when planes land at Pole, they are announced as being “on deck”; and folks eat in the “galley”. Environmental awareness, either as impact on the natural world or in terms of health for the occupants, wasn’t on the list at all, until some pesky liberals put stuff into the Antarctic Treaty. Now, to everyone’s credit, the recycling of waste materials from Antarctica is a model for the rest of the world: everything that is thrown away is separated, sorted, and returned to the US by ship. The seafloor of McMurdo Bay has been dredged to retrieve the garbage that was simply pushed into the water in years past. If a full bottle of tequila makes it to Pole, then, after the margaritas are poured, the empty bottle will begin an equally-long journey North. (Philosophically, this is an astounding waste of resources in terms of transportation, a 12000-mile roundtrip for a glass bottle, but the living and working environment at Pole warrants keeping the people happy.)

So there’s less trash in Antarctica, and that’s extremely good. But what about the smoke? Where does it go and what effect might it have?

Because of the extremely ‘clean’ natural background conditions in Antarctica, even a little bit of pollution can go a long way. In a very quiet concert hall, even the tiniest noise can be heard. Relative to the natural background, the amount of smoke discharged by the diesel power station at Pole increases the concentration of smoke to a level of 3 times the background (i.e. detectable, but just barely), over an area as large as Switzerland. One chimney, Switzerland. And when an aircraft is “on deck” with its engines idling for an hour, the cloud of brown kerosene smoke covers one-eighth of the horizon. But the dispersed concentration is so small, and the environment of pure ice is so inert, that it’s unlikely to have any effect.

Down at McMurdo, there’s a lot more smoke generated locally. The diesel generators are larger, there are more vehicles, and a lot more aircraft activity. More to the point, there’s biological life there. It’s very likely that some of the toxic organic compounds of diesel smoke will get into the food chain, into the seals and penguins and into the marine environment. Not good – but active metabolisms can at least break down those compounds. The processes of life can deal with a little bit of poison, that’s why we have livers, and because there are livers, God created onions, which are good. McMurdo is not a unique environment, much of the rest of the Antarctic coast is similar. If we have created a tiny cesspool, it’s a pimple on a large face. If a couple of penguins cough, there are lots more of them elsewhere.

However ..

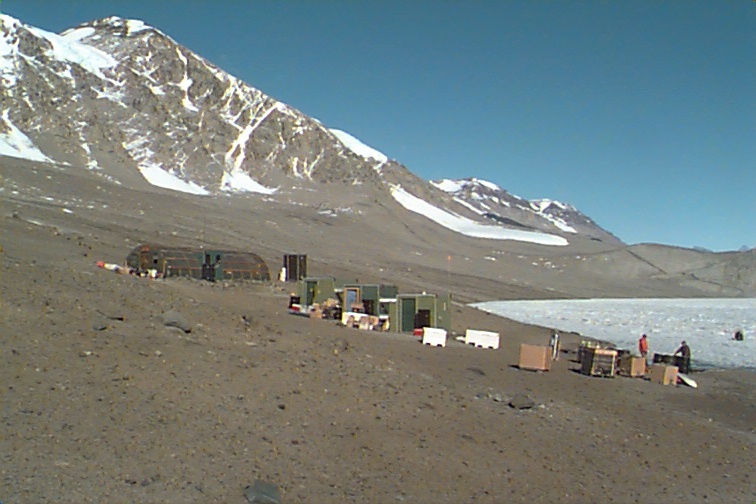

Less than a hundred miles away from McMurdo Base are the ‘Dry Valleys‘. These are an ice-free environment, a polar desert surrounded by high mountains that keep the glaciers at bay. They are almost unique on our planet: extremely cold, dry, devoid of conventional ‘soil’ nutrients – yet when the sun warms the gravel in 24-hour summer, tiny organisms thaw out, live in slow motion, constantly cold and starving, and freeze-dry again when the sun dips below the mountaintops for 6 months of winter. The king of the food chain, the lion of this environment, is a nematode, a tiny worm that is barely visible. But if these lichens and microbes and microlions can exist here, under these conditions of no food, no water and no warmth, then it is hypothesized that life may be able to exist on Mars, where the conditions are similar.

Naturally, scientists want to learn more about “Mars-On-Earth”. So what do we do and how do we get there?

We fly in by helicopter. Ever seen the smoke coming out of a helicopter?

Until recently, we powered the camps with diesel generators, and heated them with oil stoves.

We drill into the ice with two-cycle (oil and gasoline) portable engines. Ever seen the blue smoke coming out of a Vespa motorscooter?

Now the ecosystems of the Dry Valleys do indeed metabolize, but at a glacial pace. (pun intended). What takes a day of biological activity in temperate latitudes may take a year or a century under those conditions. There are the carcasses of seals that wandered in from the coast and died: carbon dating shows that the bones are thousands if not tens of thousands of years old. Everything is preserved by the cold and dryness and lack of busy microorganisms to eat stuff up. If I drop a piece of cheese onto the ground, it will still be there long after our present civilization has been replaced. Were I to wander off and perish, unnoticed, my mummy clad in red ECW’s with its attendant Leatherman Wave tool jewellery would be displayed in museums ten millennia hence, unexplained.

Now what happens if we blow helicopter exhaust and diesel fumes into this environment? Whatever does happen, will be ongoing for a really long time. Unlike garbage, you can’t pick up smoke and take it away. If these organisms are living under such highly-stressed conditions, spraying them with benzopyrene (a known toxic and carcinogen in diesel exhaust) may be all it takes to extinguish the tiny glowworm of life. And the benzopyrene won’t “go away”. If you spill gasoline on the ground at home, it will be metabolized, leached, reduced and generally dissipated by biological activity in the soil in a period of months or years at most. Spill oil on the ground in the Dry Valleys, and it will be there for your Egyptian descendants. Pass water behind a rock, and the nitrogen impact in that yellow spot will last almost for ever.

My project for the next 3 seasons will be to set up aethalometer instruments to measure any smoke that there may be in the Dry Valleys’ atmosphere arising from local operations such as helicopters, diesel generators, fuel burning etc. I am very explicitly not an expert at predicting any environmental impact, or the ecological consequences of the presence of smoke: my expertise lies in measuring the smoke and telling people that it’s there. I will take an instrument down with me and set it up near the camp in a location to try to catch a representative sample of both camp and helicopter operations: the aethalometer will run automatically for the rest of the season, and be returned next February or so.

But first, I gotta get there ………

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

I started my preparations almost a year in advance, figuring out how to set out an instrument on its own in the middle of a freezing cold desert, on the end of a half-mile extension cord, and then leave it to run unattended for 4 months. Power consumption was a real concern: there’s very little electricity at Lake Hoare and I can’t be allowed to hog it by simply carrying down ‘conventional’ equipment that you’d use in a lab at home from a wall outlet. This is the stuff of engineering, the challenge and satisfaction of defining the requirements, determining the specifications, getting the best components to do the job. Gradually the concept formed, a large black ‘transit case’ like a foam-insulated coffin. Ship it down on the plane, drag it out of the helicopter, and simply leave it on the ground with the instrument inside, kept warm by its own small internal power usage. At the end of the season, close the lid and send it home.

My son Christopher helps me, and learns about duct tape.

August. I go for my dental examination: they don’t want anyone in Antarctica suddenly needing a root-canal job. I go for my physical examination: blood, urine, and the latex-glove inspection specific to men that brings tears to your eyes and reminds you that you’ve really been to the doctor’s. All seems OK. I file my travel request and my support-services request. I’m on track, the preparations accumulate so slowly it’s almost imperceptible. I go up to the attic and bring down the box marked ‘Cold Weather Clothing’. I have the checklist from last time, what I took, what I needed more or less of. Long underwear, turtleneck shirts, flannel-lined jeans. Check. Teabags.

Two weeks away, call Travel to confirm my tickets.

“We don’t have all your medical, we need some more tests before you can be PQ’d. (Physically Qualified).

WHAT !! You don’t have all my medical stuff !! I did that months ago.

“Well, we don’t have it, you’d better go to a lab and have some more blood drawn, get them to fax us the results right away.

One week away.

“You’re over 45. You’ve got to have a Cardiac Stress Test”

WHAT !! I’ve been over 45 for 4 years, since before my first trip to Pole !! I didn’t have to do a stress test then !

“Our requirements show that you have to do the test. Get them to fax us the results so we can PQ you, otherwise we can’t issue the tickets.

So I work the yellow pages. ‘I need an exercise stress test right away – do you have an appointment time open? Today??’ . Finally I find a clinic that does – if I can get there immediately. Drive drive freeway speed limit traffic off-ramp parking lot. Stress.

In my underwear I look a lot less like a rugged Antarctic hero, a lot more like a middle-aged engineer in underwear.

“Smoke?” – no. “Drink?” – yes, couple of beers. “Regular Exercise Program?” – no. “Sports?” – no.

Clipboard entry = Sedentary White Male.

Wires attached and I step onto the belt of the treadmill. The pert, young lab technician jock looks at my 38-inch waistline, my physique so well-adapted to the slow movements of cold weather, so well endowed with subcutaneous insulation, and tells me brightly: “We’re going to run it gradually faster and up a steeper grade while we monitor your heart functions. Just let me know when you want to stop. OK?

I feel sure that she has a handcart in a closet, one of those ‘refrigerator carts’ that includes the webbing strap for securing the load, to wheel me off to the ER when I expire gasping.

It starts. A stroll – but a relentless stroll.

“No problem Mr. Hansen, you’re doing fine.

The machine whirs, the grade steepens. Now I’m hastening.

“Keep going, you’re doing fine.

Another increment. Pit pat pit pat pit pat.

“Are you OK?

– yes I’m fine thanks, it’s kind of like running for a plane – I answer as I visualize hustling through Chicago airport, a depressingly frequent occurrence.

And it occurs to me – I am running for a plane. I’ve got to pass this test before I can go to Antarctica. I am running for a plane.

The treadmill machine steps up another increment of speed and grade. I’m sweating. I’m not a jogger or a tennis jock, I’m a weekend carpenter. But the damning evidence is in the traces on the EKG, there’s nothing I can do by willpower to change the outcome. Run. Stride. Pump. Breathe. Run to get that plane.

The machine speeds up again, the traces leap on the screen.

– – – – –

Run to get that plane …..

– – – – –

Journal Entry 20 November

On My Way

Dear reader, I shall spare you an account of the arbitrary nightmare of travelling on United Airlines: suffice it to say that thanks to incorrect information, I missed my connection and spent One Glorious Day in an airport hotel in L.A.; and that my equipment box, though checked through by United to its final destination of Christchurch, could not be accepted by Air New Zealand in Auckland because their maximum per-piece weight is 70 pounds instead of United’s maximum of 100 lbs. Fortunately I am endowed with substantial reserves of patience, tact and negotiating skills, all of which were called upon. Suffice it to say, I and my equipment made it to the welcoming haven of the USAP facility in Cheech, like a serviceman returning to his unit’s base after R&R, disoriented by the confusion and anarchy of the Outside World.

Much had changed .. “Gloria’s” guest house (small rooming hotel) was no longer owned by Gloria .. she had moved away after mothering many generations of Ice People, gone south to the countryside and taken all her memorabilia, the emblems and insignia of countless Antarctic projects, the postcards and pictures all gone. The new owner was very nice, the place was certainly spruced up, but the old continuity of magic, the memory of muffled voices, the talismans of past heroics were swept away. It was as if they had spruced up Westminster Cathedral, put up sheetrock and painted everything white.

Fortunately Bailey’s Pub was still on the central square, protected from demolition either by historical designation or the sheer weight of its ambience. There was still the unadvertised discount on a pint of beer for Ice People, and the ‘Steak-With-Everything’ now had even more of Everything on it, they had added 2 fried eggs to the pile of onions, mushrooms and french fries that smother it. Too many of those and I’d certainly fail the exercise stress test, but I then realized that beer is an excellent solvent for cholesterol, and worked as hard as I could to flush it out of my system.

5 AM. Still dark, birds just starting to sing. Out to CDC and on with clothing, check in for the flight.

For some people, this is their third attempt to get to McMurdo, 2 “boomerangs” earlier in the week due to bad weather. 5 hours down, circle, 5 hours back. The loadmaster told us that conditions today looked GREAT and with luck we’d get there.

Out to the bus, out to the plane.

The flight was 5 hours of the usual mind-numbing windowless hurtling limbo, total immersion in white noise. But tolerable – or perhaps I should say tolerated. This implies either that it has got better (it hasn’t), or that I’ve got more used to it, or that the neurons linked to whatever senses were so assaulted on previous trips, are now burned out and I simply don’t notice anything anymore.

It gets to be time: we strap in: the plane dips and sighs and accelerates and swoops and we have no idea what’s out there, since we have no windows. The engines roar – are we pulling out for a turnaround? – bump and thud and the wheels are down.

Applause and the door opens to the most spectacular, breath-taking Antarctic day, the view of dreams and postcards.

Onto the waiting giant bus .. only a short trip, we’ve landed on the early-season ‘Ice Runway’ that’s just in front of town on McMurdo Sound. As the summer progresses, the ice will melt to open water, the cargo ship will come in, and aircraft operations will transfer to Willy Field.

After the reception briefing I stand outside and take in the view. It’s unbelievable, here I am again. One of the announcements at the briefing was the science groups’ meeting schedule the following day. The ‘Hansen Team’ is to assemble at 9 AM for logistics discussions.

‘Team’ ? I thought. ‘Team’ ???

I didn’t tell them.

Journal Entry 23 November

On the plane down from Cheech I had seen that there were a number of Russians on board, most of them in U.S.-issued ECW clothing. As we stretched and stood and endured the Jonah’s ride, I started chatting to them in broken Russian, yelled through the din and earplugs. “OTKUDA VY??” (where ya from?) “PITER” (St. Petersburg) “SYUDA VY??” (where ya goin?) “VOSTOK”.

Pronounced ‘Vah-stork’. And there is no comeback, no one-upper. There is no reply.

Vostok is certifiably the end of the world. Polies think they’re macho but even they wince at the thought of putting in time at Vostok. Vostok is colder, higher, more frighteningly decrepit, more threadbare and hungrier than anywhere else on The Ice. It’s at the very center of the ’round’ part of Antarctica. The atmospheric altitude at Vostok is over 15000 feet, so try breathing. The wintertime temperature sometimes falls below the sublimation temperature of dry ice. ( So why doesn’t it snow CO2? This is an interesting question of physical chemistry that many scientists flunk). Vostok is the place from which the ‘World’s Lowest Temperature’ is plotted on the maps in the Sunday newspaper. Vostok is more absolute than any outpost of the Gulag.

Vostok is a collection of wooden shacks nailed together by the Soviet Union. At this instant as I write, it has run out of fuel and an emergency flight is being staged out of Mactown to stop them from freezing to death: the Russian resupply by overland tractor from the coast is weeks behind schedule. (it’s 1000 miles and normally takes 6 to 8 weeks). The food at Vostok is said to consist entirely of starch and fat: visualize canned sardines and potato flakes. All the time. Familiar to Russians but noticed by Americans to be completely devoid of any nutritional content of vitamins or variety. No powdered milk. No communications other than patchy ham radio. No e-mail. In past years, no salaries either: the director of the Arctic-Antarctic Institute is reputed to have staked their building in St. Petersburg as collateral on a personal loan to keep the staff paid occasionally.

And these guys are on their way there, courtesy of international collaboration that transits them through the US Antarctic Program. Most are scientists, some will be there just for the season, others a year or more.

We land at McMurdo, it’s a beautiful day. We drive into town – it’s a gleaming city, bustling with shiny new trucks. Without going indoors, McMurdo already looks far more orderly and prosperous than most Russian towns. We are informed that the old ‘galley’ has been completely renovated and is now a brand-new Dining Hall. I take them in for a cup of coffee and we all reel in shock, though for diffeernt reasons.

The new Dining Hall is FABULOUS – in the most literal sense: as if out of a fable. It is huge. And new. And bright. And comfortable. Windows. Actual architectural design. No more segregation into two sides, ‘Officers’ and ‘Enlisted Men’ , the legacy of Navy days, paneling versus formica, scientists versus laborers. The new dining hall astounds me. It’s certainly much nicer than the Cafeteria at LBL in Berkeley. There are dozens of choices of food. Meat. Fish. Salad bar. Deli counter. Dessert. Fresh fruit. Varietal breads. Ice cream. Yogurt. Soup. Nuts.

But what of the Russians? The Dining Hall surpasses all but the fanciest restaurants back in Russia. Everything is free. Yet we’re in Antarctica. Politely, they say “It’s very nice”. .

A passer-by hears us speaking Russian and English and sits down. After a few moments it transpires that she is working here as a janitor, but she is a professional lawyer back home in Alaska. An avid outdoorsperson too, but a lawyer nevertheless, dress-for-success, black suit and high heels. Here she wears dungarees and pushes a broom 54 hours a week.

My strenuous work continues. Despite great personal hardship, the dictates of international relations oblige me to demonstrate the intrinsic friendliness of Americans in their natural habitat, i.e. the bar. I extend the course to include basic familiarization training in quasi-competitive socialization rituals.

The following day, I take the entire group out to Scott’s Hut. The weather has changed but for these guys it’s a spring day.

Heck, the mercury isn’t even to 10. (In the Russian winter, the minus sign is not used, it’s understood.) The wind is blowing pretty hard but they chat and point.

Back in the Dining Hall, I’m sittting with them in the lap of plenty, talking about this and that. A local comes up to our table and asks “Are you the guys who are going up to Vostok soon?”. Hearing just the word Vostok they nod, Da. He makes some fatuous comment about eating good while you can.

As his eyes take in our table, I am not distinguished from any of the others. With beard I am a plausible member of their group. I’d been chatting to them po-russkii. I could be thus mistaken. And if we were in the present anarchy of Russia, I could attach myself to their group and walk on board an Antonov with no-one really caring to count heads or check papers.

I could be going to Vostok.

Journal Entry 27 November

The weather closes in, aircraft and helicopter flights are cancelled, I have some preparations to make but I’m basically spinning my wheels. I talk to people, I talk to everybody. The mood in Mactown is very different now, at the beginning of the season, than in February which is when I’d been here before. In February, most of the population is getting ready to leave, some are preparing to stay for the winter. Those leaving, can’t wait to get out: those staying, can’t wait for the others to be gone. All have formed their conversational cliques, none wish to meet someone new. Grumpiness was prevalent, and a rhapsodic gushing beaker coming down from Pole was just an irritation.

But now, near the beginning of the season, folks are friendly and open. As always, my gas-station shirt has its oval script-cursive name patch ‘Tony‘ and that’s half of the conversational opener. I talk to janitors, I talk to managers, I talk to scientists with egos larger than Erebus, I talk to mechanics and GA’s. I am everywhere at once, because I am not going anywhere: the weather is bad, Thanksgiving is upon us, there are no flights.

We put the aethalometer outside on the snow and plug it in. It works perfectly and gradually warms up to a good operating temperature. I talk to the helicopter people, I get the safety briefings, I’m ready.

In the dining hall, I introduce my Russian friends to a USAP group who will be setting up a parallel camp at Vostok to help support the ice drilling. No, I’m not going.

We go for a stroll.

It’s a blowy, snowy, no-fly day. But our destination is another world, one that I’d never visited before in Mactown.

Just as at Pole (only larger), there’s a greenhouse full of tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce and HUMIDITY. All of which are rare.

Outside in a cargo area, a large piece of equipment stands waiting to be shipped back to the States, decorated with snow and icicles. It has pressed its last pair of trousers. But why on earth was it brought here in the first place ?? WHY did the Program decide it needed one of these?

Not too far away, a salvage box reminds us how far technology has come.

And gone.

Thanksgiving is celebrated here on Saturday, so that loss of work can be minimized and not too many people will have to curtail their enjoyment. I tried to get my camera into the dining hall but it was intrusive, embarassing, it didn’t feel right. Many people were beautifully dressed, metamorphosed from their overalls and jackets into ephemeral butterflies, seeking a transitory light. There were kilts and silk dresses and patent-leather shoes and a handsome young buck in a white tux.

The food was astounding. Forty-eight turkeys had been roasted and carved, twenty gallons of giblet gravy, uncharted expanses of delicacies stretched to the horizon. It was a SPREAD, a banquet. And with good reason: the new foodservice manager had formerly been executive chef at a resort in Vegas. He was plump and clearly enjoyed his own food.

The style, the connection were there. We were on a cruise ship, it was tropical seaspray rather than snowflakes on the outside of the windowpanes.

But I’m still not going anywhere. No flights.

I mooch over to the Coffee House and sit at the varnished-wood bar. I order a latte.

Yes, a latte.

I’m in Antarctica and I order a latte.

Journal Entry 29 November

I am here. I am at the very farthest split end of the world’s wires, a 1200-baud thread in a T1 world. A helo ride, a tiny plywood building in a vast landscape of crushed rock, but there’s a solar panel array that provides a squeak of voltage, a radio phone back to McMurdo with a modem that can be used for text in the evening, this is as far as the modern world stretches.

I am at the end of civilization’s immediate reach.

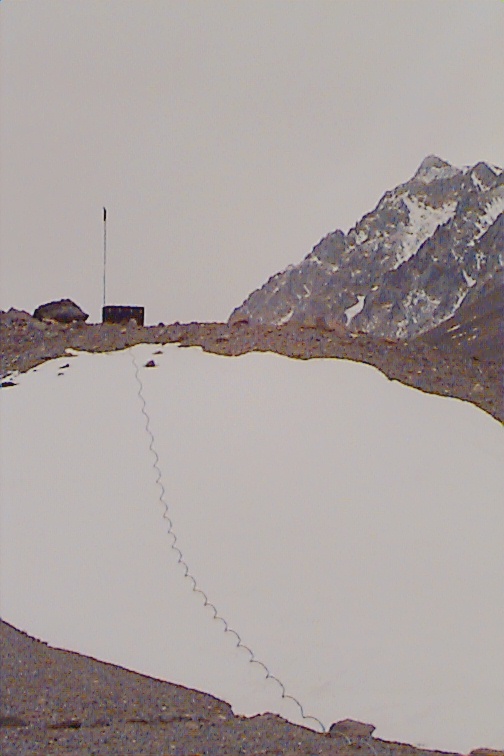

And my instrument, the aethalometer in its box looking like Stanley Kubrick’s inspiration, my aethalometer is sitting on a hillock aways from the camp building on the end of a thousand-foot cable.

The helicopter ride was too smooth, too quiet, uneventful, less inspiring than I had expected. We passed over the ice of McMurdo Sound as if swimming over a white-sand sea bottom.

But then after maybe twenty minutes we approached the entrance to the Dry Valleys. It was phenomenal: the sky here was blue rather than cloudy, the mountains gleamed on either side as we passed over a giant gravelly world flecked with unmelted patches of snow.

The first lake – Fryxell – was closer to the coast than I had expected. Beyond it, the tongue of the Canada Glacier flowed into the valley, ending in an abrupt round wall of blue ice. And as the helo flew over to the farther side, there was the tiny cluster of buildings that were my destination, nestled between the glacier, the ice-covered surface of Lake Hoare, and the scree wall of the mountains to the north.

“Your baggage has been checked through to your final destination”

Inside, the station reminded me very much of a slightly-larger version of our cabin in the Santa Cruz mountains: one large room with a divider, a kitchen and eating area, a stove, the comfortable paraphernalia of everyday life away from the city.

And the instructions were the same.

“We get all our water by melting ice in the pot on the stove, so use it sparingly.

“There’s an outhouse for solid waste, and a barrel for liquid waste (this turned out to be different)

“Minimize your use of electrical power and turn off everything you don’t need

“Wash dishes in just an inch of water till it’s really gray, then rinse in another inch

All of this was very familiar – the same strictures that apply anywhere off the grid, off the pavement.

The station building has that slight whiff of propane or heating oil, outdoor clothes on hooks, folding metal chairs, piles of boots and tables with oddments of technical equipment.

I stare at this illusion, a man working at a spreadsheet, analyzing the algae.

I look outside again.

The Lake Hoare Camp is on a patch of rocks and gravel, next to a blue-white glacier, next to an ice-covered lake, in a valley that stretches to infinity and whose slopes will never be subdivided. Every rock is exactly where it was a hundred years ago when Scott’s and Shackleton’s explorers passed through. It hasn’t rained here for at least two million years.

Nothing exists to make anything change other than the blast of wind or the inexorable creep of frost. Nothing grows. Nothing moves except ice. The lake surface freezes and thaws in patterns and spires that remind me of the tufa formations at Mono Lake.

Back at the camp, I visit the “men’s-room facility”. It consists of a black-painted U-barrel equipped with a funnel and a wooden block to stand on. Stand close, brothers, it’s cold.

The wind subsides, the sun comes out and is surprisingly hot. As if responding to a rare event, several of the camp residents run to the “beach” with their frisbee. Their bare feet scuffle the sand, they laugh and chase and play. The beach is a patch of sand between the glacier and the frozen surface of the lake, but for the moment it could be the cliffs of Santa Cruz.

Once again, I wonder. Where the hell am I? Why is all of Antarctica like this? Is it simply the place that is goofy? or is it our overlay of civilization? or is it me?- is it me that stumbles into these places, or looks at them this way?

If there was one cow-pat in Antarctica, am I the person who would step in it?

Journal Entry 1 December

A couple of years ago, helicopter transportation was provided not only by the contractor but also by the New Zealand air force. The young Kiwi pilots were a happy bunch, it was said, unencumbered by caution and eager to fly under any conditions. On two occasions they were flying when others wouldn’t, and were obliged by the weather to land in a manner that you or I would best describe as a ‘controlled crash’. However, the euphemism used to describe the reason why their helo’s had to be towed in was that they had “over-torqued the transmission”, i.e. driven it beyond its design limits in order to survive.

I was to experience this concept.

(Note: the Kiwi helo’s are no longer on The Ice)

– – – –

It was a calm hot sunny day at Lake Hoare, a Wednesday. Yes, HOT. Well, the air wasn’t very hot, but the sun sure was. The aethalometer was working great and I had some hours before I needed to check it again. There had been periods of cold clouds and strong winds, but with the fine weather I asked Rae if I should go for a walk, to hike along the valley. Absolutely, she said, take a radio and your wind gear in case, take drinking water and your urine bottle, and here are some ice creepers (a sort of velcro sandal with metal studs to strap onto normal hiking boots – and surprisingly effective).

So I put stuff into a backpack, zipped up my tent, and strode off fearlessly and cluelessly.

The center ice cap of the lake was a jumbled nightmare of eroding ice pinnacles, reminding me of something in Death Valley or Mono Lake. Apparently the fresh water runs into the bottom of the lake from galcier melt, and freezes in the winter onto the underneath of the lake’s ice cap. Ice is removed from the top by wind erosion, melting and sublimation, so the ice is constantly forming on the bottom and moving up towards the surface, where it is carved away into fantastic shapes. The process takes about 10 years and keeps the underlying water isolated from most effects of the atmosphere. The center of the lake was impassable, but around the edges there was smooth firm ice to walk on. I scrunched along and then saw HUGE ROCKS out on the center ice. How on earth had they got there? Why didn’t they melt down into holes in the ice? Some were taller than I. (I asked this question to one of the lake scientists back in camp and it turns out that this is a hotly-debated and as-yet-unresolved topic among the cognoscenti.)

There’s a mountain with 3 peaks on the north side of the valley. I was told that the peaks are named the Matterhorn, the Anti-Matterhorn, and the What’s-the-Matterhorn. After a while, I passed the end of Lake Hoare and reached a smaller lake up against the next glacier.

As I walked along on the shore, I was acutely aware of the fact that the surface of the ground was perfect : that is to say, it was a marquetry of small flat stones, each perhaps an inch or so, all laid side to side with hardly any gaps. The spaces were filled with progressively smaller gravel and sand until the surface was smooth and looked as if it had been rolled flat. (I later found out that this is due to the unbelievable winter winds).

I looked behind me: there were footsteps! – but there was not another living soul for miles! ….. It turned out that they were my footsteps: how long would they last? What had I done?

..

..

Over a slight rise, down a little slope, I came across a corpse. And then another corpse.

Each made out of windblasted bone and leather as hard as stone. These guys had taken a wrong turn down at the coast, a fatal mistake at the time. But when was that time? Which Roman emperor was ruling, which Pharaoh sat on his gilded throne, when these seals hauled themselves out of the icy water of McMurdo Sound and went the wrong way?

They wouldn’t answer. Radiocarbon data puts some of them before the dawn of recorded civilization. But time isn’t the same in the Dry Valleys. A geologist told me that some of the scree slopes have been there for three million years. It certainly hasn’t rained for at least two million years.

I hiked up the “Defile”, a narrow crack between the hillside on my left and the very front edge of the Suess Glacier on my right. Melting water dripped on me and ran along the ground in rivulets to the lakes of no outlet. I felt as if I was being extruded by the press of implacable forces.

I reached ‘Mummy Pond’, named for the mummified seals .. but I didn’t really see any, maybe they were on the other side.

The landscape, the view were incredibly sublime. I couldn’t believe I was really there. I couldn’t believe I was in Antarctica. Maybe this is what it’s like in the highest of the High Sierras, or the Rockies .. but here there were no insects, no birds, no moss, no airplane trails, no chipmunks. There was just me and a thousand-year-old seal carcass.

After more of what is probably Tibet, there is Lake Bonney with its (smaller) research camp.

But despite the setting, it wasn’t the Potala. Not at all. And the handful of people inside were nursing astounding hangovers, a combination of a sophomoric going-away party and the zero humidity. Somehow, the absence of a permanent camp manager eliminated the civilizing influence of personal continuity. These people had been camping for weeks: the domestic disorder, the empties were the proof. 101 proof.

It was a long way back.

The sun went behind the mountains and the air suddenly got as cold as it really was. The wind had been resting all afternoon, so it was ready for my face. All the way back.

Squishing past the glacier defile wasn’t fun.

Splashing through the melt pools on the lake ice wasn’t fun.

I (obviously) did make it. I even made it in time for dinner.

But I had over-torqued my feet.

Aerosol d.o.o.

Kamniška 39A

1000 Ljubljana

Slovenia, Europe

+386 1 4391 700

Aerosol USA Corp.

10157 SW Barbur Blvd Suite 100C

Portland, OR 97219 USA

+1 510 646 1600